As the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic recedes into memory, some things are left behind: discarded masks, empty vaccine vials -- and many questions about how well or not we met the challenge, as well as how to do better the (inevitable) next time.

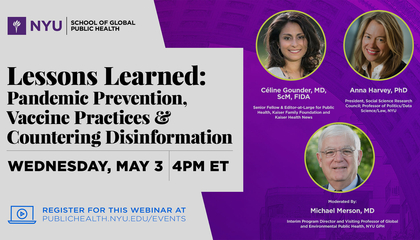

A trio of experts met recently to answer these challenging questions. Celine Gounder is a global health specialist and medical journalist with faculty appointments at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine and at GPH. Anna Harvey leads a non-profit for social science research and is a professor at NYU of politics, data science and law. They were joined by Mike Merson, a public health pioneer who has served with the World Health Organization and both Yale and Duke universities, and is currently interim director and clinical professor for GPH’s Program in Global Health.

They began by acknowledging the “crisis of competence” in our worldwide pandemic response and considering what could have been done better. Dr. Gounder said that we need to have open, honest, transparent conversations about how much money we want to spend and what kind of sacrifices we're willing to make. “It’s really a question of values. What are we as a society willing to do to save a life?”

The panel also noted the pervasive belief that Covid was an unavoidable natural catastrophe that won’t happen again -- in fact, most people want to forget that it ever happened. “How can we be better prepared the next time?” Dr. Merson asked. “That’s a really tough question for us in public health.” They considered changing the way research is funded. Right now, researchers submit proposals for their own ideas. Perhaps instead, federal agencies should identify the problems and tell researchers: Bring us your solutions and we’ll fund them.

Dr. Gounder took it a step further: We’re good at research and development, but not at implementation and equitable access; we excel in biotechnology but our health outcomes are poor. Both data infrastructure and the work force need more investment, she said; we spend four trillion dollars on health care, but only one percent of that on public health. “That is clearly an expression of our values, and that’s where things need to change.”

The panelists also discussed how to counter disinformation, which flourished during Covid. Social media exacerbated a declining trust in institutions that they agreed has been occurring for decades. For Dr. Merson, trust is key in meeting other public health challenges such as climate change, reproductive rights and gun violence. “How are we going to restore trust?” he asked.

Dr. Harvey noted that researchers are creating ways to persuade people to share accurate information. A range of solutions leverage technology, social networks and other settings where people have frequent interactions, because it’s in stable relationships that people are motivated to be good community members.

Dr. Gounder advocated for delivering health care in a credible, reliable, empathetic way. “You can’t market your way out of a trust problem,” she said. “It takes time to get there; that’s where the conversation needs to begin.” Dr. Merson agreed: “We all have a responsibility,” he said, “to be objective and try to figure out how to do better the next time.”

Questions from the audience included what the panelists would change about the pandemic if they could go back in time; what students and academic institutions can do to prevent misinformation; and whether federal agencies like HHS and the CDC need to be reorganized. To hear their thought-provoking responses and watch the entire discussion, click on the link to the video.