Dear Colleagues and Students,

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released three reports describing a bleak picture of increasing mortality in the U.S., particularly among adults aged 25-44. As a result, life expectancy at birth has either decreased or remained constant for the last three years, a trend not seen in the U.S. in over a century. While the order of the ten leading causes of death remained unchanged, age-adjusted death rates increased for seven (listed in descending order of prevalence): unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory diseases, stroke, Alzheimer's disease, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, and suicide. Unintentional drug poisonings (overdoses) comprised a majority of unintentional injuries, thereby making drug overdose deaths a primary driver of the decrease in life expectancy. In 2017, drug overdose deaths increased for the 17th consecutive year to over 70,000, exceeding the peak number of annual deaths ever observed for HIV, automobile accidents or guns.

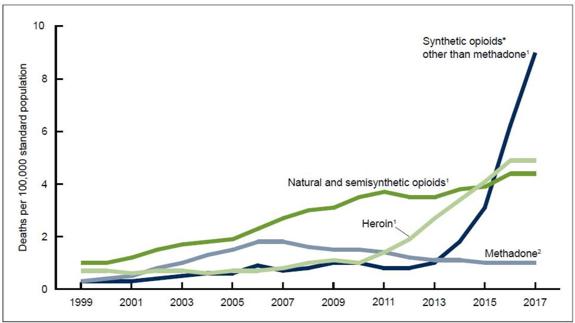

The epidemic of drug overdose deaths in the US is increasingly driven by illicitly manufactured fentanyl (IMF). IMF, a group of synthetic opioids approximately 50-100 times more potent than morphine, is mixed into illicit drugs such as heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine and counterfeit opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines, often without the knowledge of persons using them. The combination of IMF potency and unwitting exposure among people using these drugs explains much of the uptick in overdose mortality in the US since 2013 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Age-adjusted drug overdose rates, by opioid category: United States, 1999-2017. Reprinted from “Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999-2017” by H. Hedegaard, 2018, NCHS Data Brief 329, November 2018. *Deaths from synthetic opioids are primarily due to IMF.

Earlier this week, I participated in “America Addicted: Understanding the Opioid Epidemic”, a film screening and panel discussion about the current and future state of the opioid epidemic. The event, which was held at NYU’s Brademas Center in Washington, DC, featured Brandon Lavoie’s documentary, “Hometown: A Portrait of the American Opioid Epidemic”. Hometown is an intimate portrayal of the far-reaching impact of opioid addiction and overdose on a family, a small town, law enforcement and a state medical examiner. The film chronicles Shane Walsh’s trajectory into heroin use, which follows a familiar pattern. In 2004, at age 13, Shane received a prescription for Percocet after knee surgery. Liking how Percocet made him feel, which he admitted to his parents, Shane continued to use the drug illicitly through his teen years. As opioid analgesics became increasingly scarce, Shane transitioned to using heroin. In 2016, Shane died of a fentanyl overdose at age 24.

Shane Walsh’s path to heroin and fentanyl use, and his untimely death, are strikingly similar to anecdotes shared by many of our research study participants about their own experiences with fentanyl and overdoses among their friends. In our qualitative research investigating how people who use drugs are responding to the increase in IMF and overdose, we have found mixed opinions of IMF, including some individuals who seek it out because of its potency, while others try their best to avoid it. However, nearly all of our study participants report apprehension about the increased potential for overdose. As a result, they report using a variety of methods to reduce their risk of overdose, including having naloxone, the opioid reversal drug, available; using fentanyl test strips to determine whether fentanyl is present in their drugs; and getting high with or near others, including in public restrooms to increase the likelihood of discovery and revival if they overdose. At the same time, our findings reveal that overdose prevention methods are often undermined by stigma, poverty and homelessness, as well as opioid dependence and the increased prevalence of IMF.

While drug overdose mortality continues to increase in some US cities and states, provisional data from the CDC for 2018 indicates that, nationally, deaths due to drug overdose may be leveling off. In Dayton, Ohio, a city hard hit by the opioid epidemic, drug overdose deaths declined by 54% in the last year. Initiatives such as Medicaid expansion, which can increase access to substance use treatment for low-income individuals; increased availability of naloxone; peer support programs; public health-law enforcement partnerships; and, a reduction in the prevalence of carfentanil, a fentanyl analogue 10,000 times more potent than morphine, are believed to be responsible for decreasing drug overdose mortality. However, while the provisional CDC data provide a glimmer of hope, a sustained death toll of 70,000 people per year is unacceptably high. To truly turn the tide of this epidemic, we need a multi-pronged approach, focused on substance use prevention, including responsible opioid prescribing; increased access to evidence-based treatments, such buprenorphine and methadone; and, increased availability of life-saving medications, such as naloxone, and harm reduction services, such as syringe service programs and safer consumption spaces, for people who continue to use drugs. To these ends, strong public health leadership, resolute political will, and dedicated and sustained resources to reduce mortality and improve health outcomes for all Americans are imperative.

Dr. Courtney McKnight

Clinical Assistant Professor of Epidemiology