Note: The I AM GPH podcast is produced by NYU GPH’s Office of Communications and Promotion. It is designed to be heard. If you are able, we encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emphasis that may not be captured in text on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print. Subscribe now on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

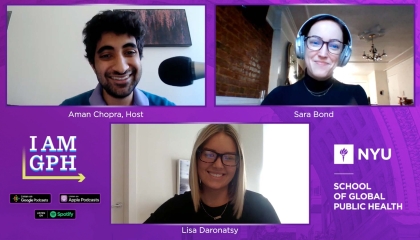

Aman: Folks welcome to another episode of the I AM GPH podcast. Today I'm very, very excited because we have a unique podcast. We have a few folks that have come from an industry out of public health and now there are students at the School of Global Public Health here at NYU. Sarah and Lisa, a warm welcome to the I AM GPH podcast.

Lisa: Hi.

Sara: Thanks Aman.

Aman: I'd love to get started by the two of you just introducing yourself and not what you're studying right now, that's a given. But rather your path, where have you come... where did you still art your whole journey and what brought you to NYU and GPH to begin with?

Lisa: Wow, great question. I can start this off. So I've been in New York for almost eight years now. I moved here to work in fashion design. So that's my background. I grew up in Indiana, I went to college at Kent State University studying fashion design. I was able to study in New York and abroad in Florence, Italy and knew as soon as I graduated I wanted to be in New York. So I started working in fashion design, loving and hating it a little bit of both. And I also started pretty consistently pursuing a fitness and health regimen through strength training, and I changed careers to be a personal trainer. So I really had been enjoying that and wanted to know what the next bigger impact more brought a change less one-on-one emphasis for me personally. And at the beginning of COVID had some, all of a sudden had a very different schedule as someone who worked almost exclusively in person. So I was finally able to prioritize applying to GPH and yeah, it just felt like the right fit from the start.

Sara: I love that story Lisa. Similar to Lisa, I've taken a pretty circuitous route to Public Health. I grew up in Florida, and then I studied musical theater in undergrad and got a second degree in Arts Administration. So during all of those, I was traveling around doing contract work, bouncing back and forth from studying abroad in London, to working in Maine, or Montana, or Orlando. And then I worked for a few years in Hong Kong, at Hong Kong Disneyland. And I was performing there and that's sort of where I was most settled in my performing career. I had just gotten off of a cruise ship contract so I was really happy to be like on land and feeling settled. And like Lisa, once I had that space to feel settled and breathe a bit, I started looking ahead to what was next. And I had always thought I wanted to go back to school for my masters in acting or directing and then teach, and realized that it just didn't resonate anymore. Like Lisa, I had also started pursuing fitness and health things on the side. I was a certified yoga teacher and a certified nutritionist and started looking at perhaps RD programs, and then I found public health and that really resonated with me because it was bigger than just talking to one person. It was fixing systemic issues that I knew caused this person to absorb these false beliefs that were causing them so much distress about their health. So I found GPH right at the beginning of the pandemic and I applied, and here we are.

Aman: Wow. So both of you have come from completely different angles and fallen into this similar path. First off, it's fascinating to hear how multifaceted the two of you are, which is so exciting to see how these interests have come into this one direction. I'd like to dive deeper into that direction. There was this... I'm a GPH, both of you mentioned that. What was the catalyst that got you to take the path for GPH going down the line back in 2020?

Lisa: I guess for me it was I work a lot with my personal training clients nutritionally kind of similar to Sarah coaching people one on one, and started I guess to think like, why does everyone have the same misconceptions about fitness, nutrition and health? And started to question that in a bigger way. And I think realized that while nutrition seemed... And I love to cook I know Sarah does too. And I felt like, a registered dietician was more of the same thing of really just focused one on one and not really starting at the root cause Kind of wants things. Although it might be preventative in many cases, it didn't seem like it was the upstream start of where things are tough for people. So understanding that, I didn't really... And for years I'd looked at RD programs as well and I was just not interested in taking biochemistry again, since I hadn't been in the biochem class probably since high school or whatever... long time. So over a decade I was a little nervous about that. And that part just felt right once I found like public health — it just was I guess the intersection of things that I cared about and things that I felt like I wanted to work in.

Sara: Yeah, then that might be something that helps folks that are deciding between an RD track and a Public Health degree. I knew that I didn't want to do clinical work. So that was really what made the shift for me. Yes I didn't wanna take biochem either, but we could have figured it out. If we had really wanted to in a hospital setting, crafting these medical nutrition plans for people, we would've figured it out. But I knew that that wasn't the kind of work that I wanted to be doing. Similar to Lisa, an example that I like to use is I was spending a lot of time telling women they didn't need to be afraid eating bananas, and I realized I don't wanna keep doing that I wanna figure out why are all these women terrified of eating bananas? Because they think there's too much sugar in them. Where did we go wrong here? So clarifying all of those things, and a big part of it for me was because food has always been a storytelling vehicle in my life. It's always been a way that I connected with people, that I shared intimate experiences in different parts of the world. A way that I felt grounded where I was. I moved around a lot and my feet felt very planted when I was eating food made by people there, grown by people there, that tasted like the place. And the fact that our current food system is set up in a way that people are robbed at that experience, really deeply hurts me because I want them to have that deeper connection because it's brought so much to my life. And also not just I want them to have that, but I want them to not have the fear, the confusion, the regret, the debt. The amount of money that we're spending trying to feed ourselves well and trying to be healthy when it doesn't have to be that difficult. So all of those things sort of came together and public health seemed like the answer at that point.

Aman: I'm not only hungry, I'm also inspired. Great. So the two of you have come, as we mentioned from different directions, and I'm sure there's a lot of listeners that are interested in this area as you two are in your own way. How have your experiences in your past field given you advantages applying to a course like at the Public Health School?

Sara: I think that coming from another field and coming to grad school, after having a little bit of a break between undergrad and grad school, you learn to trust your gut a little bit more and you may not know exactly what it is you want, but you know what you don't want. So that was really helpful. And I was sort of feeling things out and trying to trust my gut about what was coming next, and I actually heard an I AM GPH podcast. I swear to you, I heard it, I was looking at all these goals and I heard an I AM GPH podcast with Niyati Parekh and Arlene Cruz. And they were describing the course that they teach that's all about global determinants of health, social determinants of health internationally, the double or triple burden of about nutrition. And I was like, this is it, like this is it. I know that this is right. And because I had diverse work experiences, I knew that I could trust my gut when I felt that like lightning strike of this is work that I'm meant to do. And coming from a theater background actually has been really helpful in a lot of ways. I've always been my own boss, I've always had to keep track of my own audition schedule, be very organized, be very self starting and take initiative. I think you have to do those things in graduate school and in Public Health, but I've also worked on teams. I've worked in large casts, small casts, I've had to take direction from peers, which is something that we need to do a lot as well. And being a theater artist is being a communicator. Is being a storyteller, whether you're singing, whether you're dancing, reciting lines, etc., you are communicating with people. And that's so much of what Public Health is. So the skills have been really applicable in ways that I didn't know that they would be at first.

Lisa: Oh, love hearing that Sara. Similarly for me, I had quite a gap between undergrad and graduate work so I feel like I got to bring a professional side of firsthand experience that I would not have been able to be as great as a contributor, just personally, to teams to the work that I was doing in school. And I think a lot of times in our life, we think that we have to have the whole route planned out, from A to B, from where you start to where you wanna go. And I think sometimes you just get like a feeling kind of like Sarah said, or you get a glimpse of what things could be or a path that might be for you. And I kind of felt that way. Learning about GPH and public health in general and knowing that yeah, I wanted to make change that was broader than just working in a one-on-one setting. Someone actually had introduced me to the public health like pyramid of impact. And I think that that seeing, where the biggest impact could be for me while I loved working one on one with people at the top of the pyramid in personal training, it was just at the top. So it was just so focused and so specific, which now I think we need all of it, but I feel really called to do that. And the design part, everyone wants beautiful graphics on everything these days. So that part has been fun of like, "Oh yeah, I can do that. I'm pretty good at Photoshop and Illustrator."

Sara: I have a few classes with Lisa, and we're always the ones in our group projects like I can do the slides, like I got it. No problem.

Lisa: Please, please no more times enroll on these slides guys. We can do better.

Aman: I'm loving this left brain versus right brain concept that you folks are kind of addressing, what is the balance of art and science? Everyone seems... When I thought of public health to begin with, I think of very robotic, very structured when I go to hospital doctors, how are these creative elements that you two have in your past benefiting you in this very science oriented environment right now? Apart from being really good at illustrator in class there. And as Sarah, you stated theater arts is communication and we are effective communicators because of theater arts. Are there any other thing that you have noticed a moment that each of you have that you can walk us through? That you have experienced that, "Whoa, I can't believe that this concept has applied so effectively in Public Health and no one talks about it."

Lisa: Well, I think exactly to Sarah's point of being like able to communicate, even graphics are communication tools, right? So we see that there's a need to translate science into information that everyday people can apply to their lives. So being able to be a strong communicator and someone to be in that intermediary, "Hey professor, what you said is this, now that me it and deliver it into..." Those tools are invaluable. And when you aren't translating that message well, it's confusing for people. For everyday people who are the ones that were trying to help and make an impact in their lives. And so I think that's maybe not my first thought, but certainly an important one.

Sara: I'm gonna tell a small story, because I think that it directly relates. In undergrad on my voice teacher's office door, where I would walk in to go to my voice lessons. She had a piece of paper with a quote, there was something along the lines of the two actors walked off stage and the woman said to the man, "They didn't laugh when I asked for the tea." And the man said to the woman, "That's because you asked for the laugh, not for the tea." So presumably during this scene, the woman asks for the tea, the audience always bursts into laughter, but if she becomes accustomed to that, and she knows that the laugh is coming and she feeds into it and she has the scene all figured out in her head before it even happens, it loses the electricity, right? It's not real. She is not listening, she is just waiting to talk, and to play out the scenario that she has in her head. And as public health professionals, that's something that is our calling, something that we need to do and something that we need to avoid doing. If we decide the intervention that a population needs before we go in into it, before we've spoken with stakeholders, before we've looked at all of the unique factors that impacts this person, that impacts their community, that might have such a different lived experience than us. We will not be effective. We will end up with programs that are drains on our resources and waste of time, and don't help people or create meaningful change. And I think that those lessons of listening louder than you speak and going into every day as if it is fresh and nude and asking for the tea rather than for the laugh is really a direct lesson for me. And I've seen that play out in case studies and in coursework, but I also work as a researcher at the College of Dentistry. Interestingly enough, I do nothing with teeth. I'm working on breast cancer research, but we've conducted a few focus groups and I've seen that come up in my focus group work, not entering into these intimate conversations with our participants already guessing what they're going to say. And instead being really open and receptive to where they lead the conversation, asking open-ended questions, and using motivational interviewing to see where their head is really at, rather than asking guiding questions and getting the desired outcome.

Aman: Beautiful. That that's a lovely story. I'm gonna use that myself going forward. Nice. So there's this element that you mentioned of, of outcome dependence. I want to go into the belief system of a student that's in the same shoes as probably each of you where we mentioned earlier that sometimes this program seems very robotic and there's not much creativity existing when people think of doctors or something to do with public Health in general. What would be some piece of advice that each of you would give to a student that has this creativity, has their own unique sets of skills, but has this deep interest and desire to be a part of the public health space and have an impact?

Lisa: Yeah, I'd say that being multifaceted and having different layers of yourself, is it only to your benefit? Whether you realize it or not every experience that you have and you bring, make you so unique and have such a different perspective and different length on issues and things that come up in public health and knowing that you don't have to fit into a robotic box, I think in anything. And I think, especially in our modern world today, so many people are realizing that they are the greatest benefit when they can bring almost every part of themselves to their work and to what they're passionate about.

Sara: And public health people are usually really good people I have found. So if you are passionate about public health, and you think your skillset doesn't apply, they will teach you. Like I remember one of my professors saying, "I can teach anyone the basics of epidemiology and of biostatistics. I can't teach you to love this, and to want to make a difference." So any creative skills that you have, any passions, any hobbies, they can all be part of it, there's room for all of it to fit. And I think that our differences are definitely our superpowers and what sets us apart. And there's something that I felt really self conscious of and nervous about when I entered the program, definitely felt that impostor syndrome. I was like, "I'm, you're a girl at sand time trivia, but I don't know anything about the brain." But the longer I'm in it, the more I realize those things really help me contribute meaningfully.

Aman: Lisa, I'd like to hear from you about impostor syndrome a little bit more. Have you experienced it in this course? And what have you done if something like that does occur with you?

Lisa: Yeah, I have done a lot of work on impostor syndrome bleeding up to being in this course. I think that when I started, I didn't really feel it as much starting this program, but I'm also a little bit older of a student, and feel just more sure of myself in general, but I definitely remember feeling it when I started personal training. I am like, "I hardly remember the muscles. Like I know this exercise should look like this, but... I know your bicep is here, your tricep is there, but..." So I definitely felt that more when I started, when I had completely left my previous industry of fashion. So I can tell you anything you want about French scenes and flat belt scenes, and knitting, and two by two ribs, and whatever, tell you all that stuff, but I didn't have a great confidence when I started doing training. And that's when I felt it more. And I think in that time between starting training and starting at GPH, I'd done a lot of work to dismantle that within myself, which mostly just included lots of reading and reflecting and yeah, and building my confidence over time personally.

Aman: Love it for the folks listening, don't shy away from your dreams and desires to be a part of the global public health area, because it's wonderful there's always something for everyone. So please consider if you're even thinking about it. impostor syndrome is totally fine. And this course, or courses like this will help you combat that going forward. The last question we usually leave for guests, just for some things to think about food for thought. The public health, the public health space has a lot of amazing things that does it all it also has a lot of problems we need to fix. If each of you had a magic wand, what would be the one problem you'd love to fix right now in the world? Or something that you're involved in that you'd like to share with the listeners.

Lisa. What a loaded question. My gosh.

Sara: I know. This isn't like a magic wand where we can like conjure more magic wands.

Lisa: Yeah.

Aman: I'd love to hear what you come up with.

Lisa: I think my magic wand would be really focused on upstream factors. So getting people things like increasing socioeconomic status, reducing poverty, housing, affordable housing, things that would really make a big impact downstream.

Sara: I will be, I guess a little bit more specific because this is just the current hill that I like to put my flag in is I would eliminate sizeism and fat phobia in medical literature and practice. As a society we have adopted a very Eurocentric and therefore racist and colonialist view of what healthy bodies look like and that's really impacted our ability to come up with effective and equitable interventions for people. We've misconstrued thinness and health, and we've applied a lot of morality on the shape and size that people show up in, in their body. So if I could just wipe all that out and help people focus on health from bio markers that actually matter, like with their blood pressure, with their glucose, their quality of life, the quality of their sleep, quality of their community and their social interactions, that would be the one thing that I wipe out. I think that the language of obesity research is getting dated and that we can start to be a lot more specific with the kind of research that we're doing and the health problems that we're trying to tackle.

Aman: Lovely, lovely. Thank you both for sharing that. Thank you both for sharing these answers there, and thank you both for being a part of the interview. It's very insightful, it's very inspiring. I'm sure that someone like Sarah in the future will also listen to a podcast and probably join NYU or find their GPH path, whatever that is for them. So Lisa and Sarah, it's been truly wonderful to have you two on the podcast, and thank you so much.