Note: The I AM GPH podcast is produced by NYU GPH’s Office of Communications and Promotion. It is designed to be heard. If you are able, we encourage you to listen to the audio, which includes emphasis that may not be captured in text on the page. Transcripts are generated using a combination of software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print. Subscribe now on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

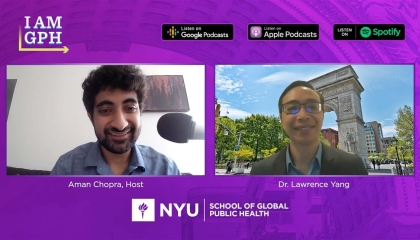

Aman: Dr. Lawrence Yang, welcome to The I AM GPH podcast, we are glad to have you here.

Lawrence: Hi, thank you so much for the invitation. I'm really excited to have this opportunity to speak about all the new work that's happening at NYU GPH in global mental health and wellness.

Aman: Amazing. So, let's just hop right in into what we'd like to talk about. You've been working in the world of mental health and stigma for a number of years now, could you give us an overview and for those of us that are perhaps not familiar, how exactly can we define mental health and stigma?

Lawrence: Yeah, that's a great question and something that's so important now, especially given the pandemic and the way that it's affected mental health and populations all over the world, obviously including in the United States. So mental health we can really think, or mental health challenges, I suppose, the converse of it, we can think of it as anything that really impedes optimal, I guess, functioning in the world, right? Or wellbeing in the world. So what are the things that could lead to impairments in terms of one, functioning to their fullest capability in their lives, in their daily lives. So this can include things like depression or anxiety, or when you talk about more severe forms of mental health challenges, it can get into things like psychosis or psychotic like experiences. So stigma are the conceptions that typically unfortunately, negative conceptions that are associated with any of these mental health challenges. So for instance, what do people typically think about a person who's experiencing symptoms of depression or anxiety or psychosis? And unfortunately, these types of conceptions are typically quite negative and can really impact the person in a negative way.

Aman: Okay. So the big question that comes to my mind is how does one measure stigma?

Lawrence: Great question. So, I can go on about this. I will, in a nutshell, stigmas are really diffuse and complex concept, and stigma can occur on many different levels. It can occur on the individual level. It can occur on the community or the public level. It can occur on the policy or structural level. And so we have ways of thinking about and measuring stigma for each one of these levels. And honestly, each one of these levels merits its own separate conversation but scholars, including myself and researchers are constantly basically thinking of ways, new ways of conceptualizing how stigma occurs across these different levels and then how we can most accurately measure it.

Aman: Wow. Okay. So you did mention in the beginning that COVID has certainly given us more awareness and made it more acceptable, but are we actually making progress here with regards to the whole topic?

Lawrence: Yeah, so that's an open question. I think, and that's something that I've been giving some thought to. I think that what COVID has allowed us for to do is to really more openly talk about loneliness and how loneliness affects our mental health and our wellbeing, just because everybody's engaged with this now, we're all separated, cut off from other people in a way that we weren't just two years ago. And everybody's struggling with this to some degree. So I think the opportunity is that mental health challenges, everybody has really firsthand experience with it right now, at this particular moment. So, it is an interesting question though, in terms of has it allowed us to make progress with mental illness stigma per se. Now that's another, and I think, perhaps separate question, and I think that that's something that we hopefully can take this moment and really push forward the broader field. I don't think we've been able to capitalize on that to the degree that we might be able to, but hopefully, again, work that I'm doing, work that other researchers that I know of are doing will be able to capitalize on this moment.

Aman: Lovely. Let's hop right in into your work. I'm curious to learn more about the Li Ka Shing Foundation and for those of us that have no idea about it, could you just give us a brief summary of what it is it all about?

Lawrence: Yeah. So first of all, I really want to just with the deepest amount of appreciation thank the Li Ka Shing Family Foundation for providing a very generous donor gift to NYU GPH that I have the great honor to administer. So what this gift does is it really puts global mental health and wellness on the forefront of the work that we're doing here at GPH. And what we've been doing, well, so this initiative actually grapples with a lot of the issues that we've already started to speak about during this podcast. Let me jump into some of the activities that we've been doing in the first six months of this gift, which runs for two years. And so the first set of activities is that we have actually sponsored a set of pilot awards to the faculty who are working in this area. And so there's some really exciting work that's happening, I'll just give you a couple of examples. One of the pilot awards has been given to Dr. Peter Navarro. He is doing a project to meet the mental health needs of trafficked children and adolescents in Vietnam. And so what they're doing is assessing the integration of this technique called photovoice and looking at its impacts on uptake of mental health services. So photovoice is basically when people utilize photographs in this way to depict a narrative of their own experience. So you can just imagine how powerful this could be in terms of trafficked youth who are coming into Vietnam, telling their really stories of resilience and, again, grappling with, but hopefully overcoming the challenges that come with having survived the experience of being trafficked. And essentially, he's utilizing this method to really enhance mental health uptake in this very, very vulnerable group. So that's just one example. Another example of a project that we're piloting or seating is from Dr. PT. Le, she's an assistant research scientist at GPH and PT is doing this fantastic work on piloting a mobile self-help app for cancer patients in Vietnam. And I also just wanna mention that actually, Dr. Le with support from this generous gift has actually received this very prestigious award we call it, it's actually called a K Award from the National Institute of health. And so she has a five year project actually to expand and look at this work in Vietnam. So she won this really prestigious award, it's $800,000 over a five year period. So, just some snapshot into some of the really fantastic pilot work that's happening. So the second set of activities are, we just are in the process of awarding set of fellowships to our masters and our doctoral students. So again, from this really generous gift, we are able to give support to up to six master students this year and then three doctoral students this year who are doing work, again in global mental health, wellness and or stigma. So basically, and so the way the fellowship looks is that the fellows participate with a faculty mentor, they work with them, a mentor from our group. And so they work with the mentor fall and the spring and culminates in a project in the summer where they spend full time working with the faculty mentor, pandemic allowing, they also travel to the site or a site where the work is occurring. And this provides an incredible training experience in terms of being able to immerse themselves firsthand in global mental health work. So just a couple of examples of the kind of work that this fellowship is supporting. So we have one fellow is doing work among South Asian severe mental illness in New York City. And looking at how cultural barriers impact access to care. Another fellow is doing work on, for instance, the COVID-19 pandemic and the mental health effects on Asian-American essential workers in the United States. So again, just to give you a sense of the diversity and the range of the topics, but it's so exciting that our students now will be able to engage directly in these topics due to the, again, this generous gift.

Aman: That is... Go ahead.

Lawrence Oh, no, I'm sorry. Go ahead, please.

Aman: I'm saying that is amazing. I mean, you have just touched the surface of whatever we're doing with this foundation, and there's so much to offer. What I'm curious to hear, Dr. Yang more is what started your journey? How did you get into the space of mental health and being, because there is clearly a passion to your voice when you're talking about administering these things and the way you can describe each individual project. So I'm curious to hear a little bit about that.

Lawrence: Sure, absolutely. So just a bit about myself. I grew up actually outside New York city, so about in Westchester county and at the time, it wasn't terribly a diverse place. And so I grew up as one of the only ethnic minorities within my school, my town, and that had a profound effect on me in terms of the way that I felt different and alienated within my school. I did actually have a good friend group, a solid friend group, and that was very helpful, but all the same, I think just culturally, I just felt very different just growing up in the setting. And I that that really stayed with me all throughout my development. And so in college and in graduate school, it was just an obvious choice to me to choose psychology, mental health. And then how culture really impacts mental health and stigma and wellbeing. It ties so deeply to my own experience. So I've taken this work when I did my PhD in clinical psychology in Boston university. I spent two years in China, in Beijing, China, and really understanding the way that mental illness, the way it looks, the way it's experienced by people with psychosis and their family members. In China, I saw the cultural impact, the way that the family members and the people themselves just felt so marginalized and alienated from society. And while my experience of course, was different in many respects, there were some similarities just in terms of feeling that profound sense of difference. So, the work that I do comes from a very personal place. I believe it's something that is really fuels the work that I can do in the world. And I hope you enables me to approach the work in a more compassionate way. And again, it's something that I've dedicated my life to and it's something that I'm lucky to be able to actually dedicate my life to.

Aman: I love that, I love that. Very, very relatable as well. Thank you for sharing that. You mentioned a little bit about cultures and I'm curious to know as you briefly touched upon certain Asian countries where the concept of mental health is not as well defined, if you will. What are some countries we could learn from that have actually kind of gotten it right when it comes to the topic of mental health?

Lawrence: Great question. So I'm gonna take your question in two ways. So I'll answer it, number one, another area that I've done a lot of work on is basically a stigma of that at risk for mental disorder. So happens if you're identified as is being at risk for like a serious mental illness psychosis. So I was fortunate enough to get a five year or a one grant from NIH to study this topic and to really try to bring stigma to new areas. So basically these youth are identified as being at risk for developing psychotic disorders, but they don't actually have psychotic disorders . I will say that the United States actually took this marvelous work that was done in Australia, Australia pioneered all of this work, a good 10 or 15 years before the US started to do this work. And so that is one example of an area when mental treatment and mental health really was done in a spectacularly innovative way in a new area. And then the US has adopted it. I'll take your question in another way though actually, if I may, and just talk about how we are utilizing some of the understandings that I've developed in mental health and stigma, how I've developed that in Asian groups in the US and actually taken it globally. So, some of the core work that I've done is in this concept of what matters most, and this borrows deeply from Arthur Kleinman's work from Harvard. I had the incredible opportunity to work with professor Kleinman as part of my training mentored research award, this is called a K award, but basically Dr. Kleinman is a renowned medical anthropologist. And I had the chance to work with him to understand culture and stigma and how those two things intersect. So in a nutshell, culture shaped stigma in that culture impact, excuse me, stigma impacts everything, but where it hurts people the most powerfully are upon these capabilities that matter most in their local cultural setting. So, I'll take this concept and just talk about it a little bit in two different settings that I've had the opportunity to do work in. So in my K award, I did work with Chinese psychosis who live in New York city. So this was after I went and did my dissertation. I lived in China for two years, I came with that knowledge, that cultural knowledge, and I brought it back to the United States and to New York city. And so what matters most among a lot Chinese groups is lineage, is actually perpetuating the family lineage, making sure that it has resources, that it has honor, face, et cetera. And even though this changes is in the process of changing in China and in Chinese cultures, it still is an enduring cultural orientation that a lot of Chinese groups have experienced. So, I was able to use that concept and really work with the Chinese group in New York city. I've also taken the concept and actually taken it globally. And so most recently to the context of Botswana. So, Botswana is a country in Sub-Saharan Africa, has among the highest prevalences of HIV in the world, about anywhere from, well, depending on the estimate that you look at, anywhere from 20 to 25% of the entire population has HIV. So it's a really huge public health issue in this country. And we've taken this concept of what matters most, and we've seen that what matters most in Botswana is heavily gendered. And so for women in particular, what is seen to matter the most among women in Botswana are capabilities of taking care of the household. It's heavily gendered, and again, these things are changing, but there's a strong thread of traditional sort of gender roles in the society. So what it seemed to matter most for women is exactly caring for a child or bearing a child and providing a safe and thriving household. If I can, sorry, I should have said more about this. So the thing that's important about this concept is that it really gives us a way to understand how culture shapes the way that stigma is experienced. So, to utilize the Botswana example, so, pregnant women with HIV would experience stigma in all sorts of domains of their life, right? It could happen in a or potential job. It could happen in community, family, within themselves in terms of self stigma, but what matters most, framework enables us to understand the way that stigma most impacts individual is actually through, again, through their ability to bear and raise a healthy child, and then to provide a thriving household for that child. So that's the way that stigma's most powerfully felt by these individuals. So what's exciting about the framework and the concept is that it enables zero interventions towards promoting these capabilities specifically.

Aman: While we have touched, we've barely even touched the surface of all the amazing knowledge you have to offer. I've learned so much in the past few minutes, and I know that there's so much more to learn. So since we have to end the podcast right now, I'm curious where we could, where someone who's interested can learn more and dive deeper into this whether they're, not only an NYU student, but even a listener from outside, where could we learn more and make ourselves more aware and contribute to something like this?

Lawrence: We actually have a dedicated website to the global mental health and stigma program, and we will make sure to provide it to you. And this describes a lot of the activities that are being undertaken right now by myself and also our dedicated faculty to this issue at GPH. So we have a core set of faculty who are doing really just groundwork and work in this area. So, I invite anybody to please take a look at the ongoing projects that we have either on this website and then take a look at each of the faculty members' individual work. So, that'd be number one. Number two, I would just invite people to exactly just, you know who teaches a fantastic class in this area is actually Emily Goldman, one of our faculty, Dr. Emily Goldman is actually called a global mental health. So I think that that would be another fantastic potential academic resource. And then lastly, I think is just really just being aware of all the different work and activity that's happening in the world right now. There are a lot of efforts to try to counter mental illness stigma in all of its different forms. There is work that's occurring, let's see, through, California had this tremendous statewide campaign to try to end mental illness stigma and that ran for several years. And I think it's called Each Mind Matters. It's either Each Mind Matters or Every Mind Matters. And people could take a look at the materials that were generated from that campaign. I think that's also tremendous resource, I had a chance to work with them actually during the course of that campaign. And of course, if you are interested in this work, feel free to reach out to me. This is the work that I hope to promote again, throughout my career and work and especially through the work at NYU.

Aman: Lovely. With a short but very, very sweet podcast, thank you Dr. Yang for an amazing detailed amount of information and an awesome conclusion where we can go and find out more ourselves. We love to have you on this podcast.

Lawrence: You bet, a real pleasure. I'm happy to join, take care now.